IN THE CENTURY following the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes the numbers attending the church fell away with the passing years as refugees died, dispersed and merged with the local population. Many transferred to the local Anglican parishes; others joined the early English 'nonconformists'.

Our church suffered its share of schismatics – a disease all too common among ecclesiastics of all ages. Several separate and independent French-speaking churches were established in Canterbury over the years – all have since faded away.

Gradually the crypt became too large a space for the congregation and the cathedral authorities over the centuries pressed the French church to occupy smaller and smaller areas. In about 1825 the church was moved to the south aisle. The pasteur at that time, Jean F Miéville, was decrepit and blind and the church was struggling financially and numerically. Understandably, the dean and chapter of the cathedral wished to resume use of the main crypt area. To reserve so much important space for such limited use seemed wrong.

The south aisle chapel was fitted with box pews. A new pulpit, complete with sounding board, was placed by the windows – catching the natural light – unlike its predecessor which stood some 18 paces northwards in the heart of the crypt, where marks left by its base on the stone floor can still be discerned. How many candles those earlier preachers must have burnt as they prayed and preached there for hours on end. No wonder Pasteur Miéville went blind towards the end of his long ministry – the longest in the history of our church – so far !

In his latter years Pasteur Miéville took the service once every three months preaching as best he could and celebrating communion. On other Sundays, the liturgy was read by a layman.

After Miéville’s death the French Protestant Church of London came to our aid – as they have done more than once in our history – mustering a team of pasteurs who travelled to Canterbury once in every month. Before the railways reached the city in the mid 1850s, this journey had perforce to be made by horse and carriage – such energy and enthusiasm has kept our church going for more than 400 years.

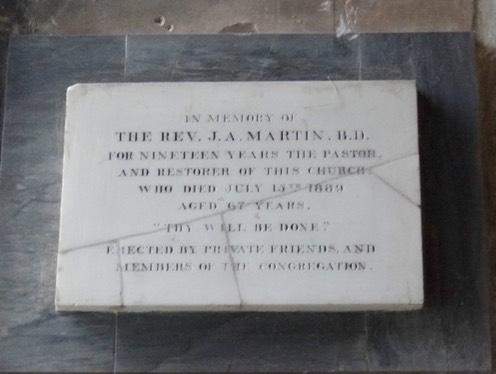

One of the team was Pasteur Joseph Martin, who, from 1875 settled in Canterbury and changed nearly everything. By public subscription he raised a large appeal fund to refit the chapel. The box pews were taken out and pews in long lines were provided instead. The arches were painted with biblical texts in Gothic style polychrome. A new pulpit, font and communion table were introduced and ‘proper’ gas fittings installed. Some relics of those days can still be seen in the main crypt. Just outside the chapel, the arch facing the door in the south aisle retains its text and coloured decoration and there are vestiges of Martin’s decorations on the arches near the marble tablet in his memory, by the window where his pulpit once stood.

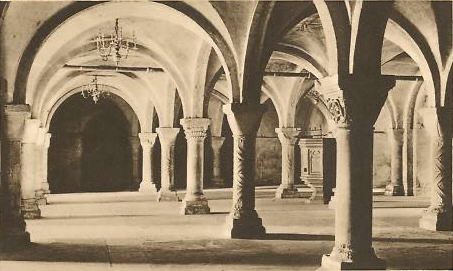

The south aisle of the crypt (facing west) as refitted by Pasteur Joseph Martin in 1875.

Pasteur Martin’s vigour extended to the production of a book of historical articles and a complete new liturgy in a well-produced service book. At the same time (with the aid of the archbishop) he conducted a campaign defending valiantly the independence of the church against those outsiders who wanted to wind it up and merge its assets with his old pastorate in the Church of London.

Naturally, he was at the same time protecting his own position in Canterbury. A man of energy and determination, he was prone to independence of action that sometimes upset even his own flock. On his deathbed the poor fellow was forced to receive the members of the church consistory who wanted confirmation that he had indeed ordered a new and larger organ (from Messrs Browne of St Mildred’s in the city) to replace the old one. Almost with his dying gasp Pasteur Martin confirmed that he had done so.

The reaction of the consistory is not recorded but the organ is still with us bearing the date and the makers’ name. The same firm still maintains the instrument for us so the Pasteur’s order was presumably honoured – unlike that for the hymn books produced by Gibbs the printer – one of the church trustees. At successive meetings after Martin’s death, it was decided repeatedly not to pay for the books which apparently the late Pasteur had ordered without authority. Poor Mr Gibbs!

After Martin the church again had a succession of short-term pasteurs and the dean and chapter of the cathedral, having received a legacy of £1,000 to refurbish the crypt, took the opportunity to press the church to retract still further by withdrawal to the Black Prince’s Chantry. The discussions took five years. The result was a refitted chapel, mostly re-using the pine pews and communion table installed by Joseph Martin together with new fixtures of good English oak all made by Richard George Ditton Parren, whose grandson maintains to this day his family’s association with the church, stretching back over three centuries.

The transferred fittings, including the font and the organ, look remarkably well in their second home – as if purpose-made, in fact. Certainly the arrangement of the pews is far preferable to that adopted previously in the south aisle. They now face the pulpit instead of each other.

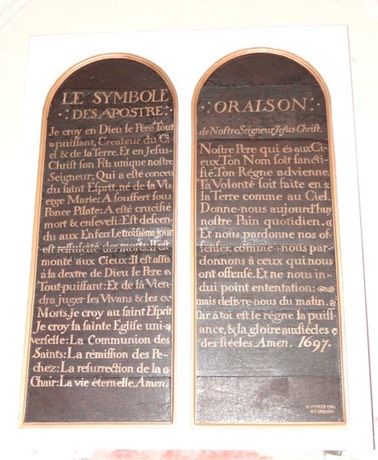

Our oldest fittings are of course the boards setting out the Lord's Prayer, the Creed and the Commandments. Such boards were common in the 17th century throughout Protestant Europe. Some are still to be seen here in England, notably in a few of Wren’s wonderful churches in the City of London. Ours must be the only French version in this country surviving from that period. Now in their third location in as many centuries, they overlook our communion table – just as they did in the main crypt long ago.

There are two large oil paintings; on the organ case, facing the entrance is Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, 1519-72, a leading Huguenot hero. This statue of him depicted in the painting has stood since 1889 in the apse of the Temple de l'Oratoire, Rue de Rivoli, Paris.

In the vestry hangs a re-interpretation of the engraving by Jan Luyken 1696 The Flight of the Huguenots, a details from which appears in the heading of our website. This version, by J Johnson dated 1866, is said to depict a group of refugees landed at Dover. Clearly the artist had never seen Dover castle but some of the figures portray vividly the desperate misery of refugees throughout the ages – a salutary reminder of the origins of our church and of those suffering similarly today. The painting was restored and cleaned in the 20th century by J Hoad of Canterbury.

© Michael H Peters 1992